Types of Primary Medical Research

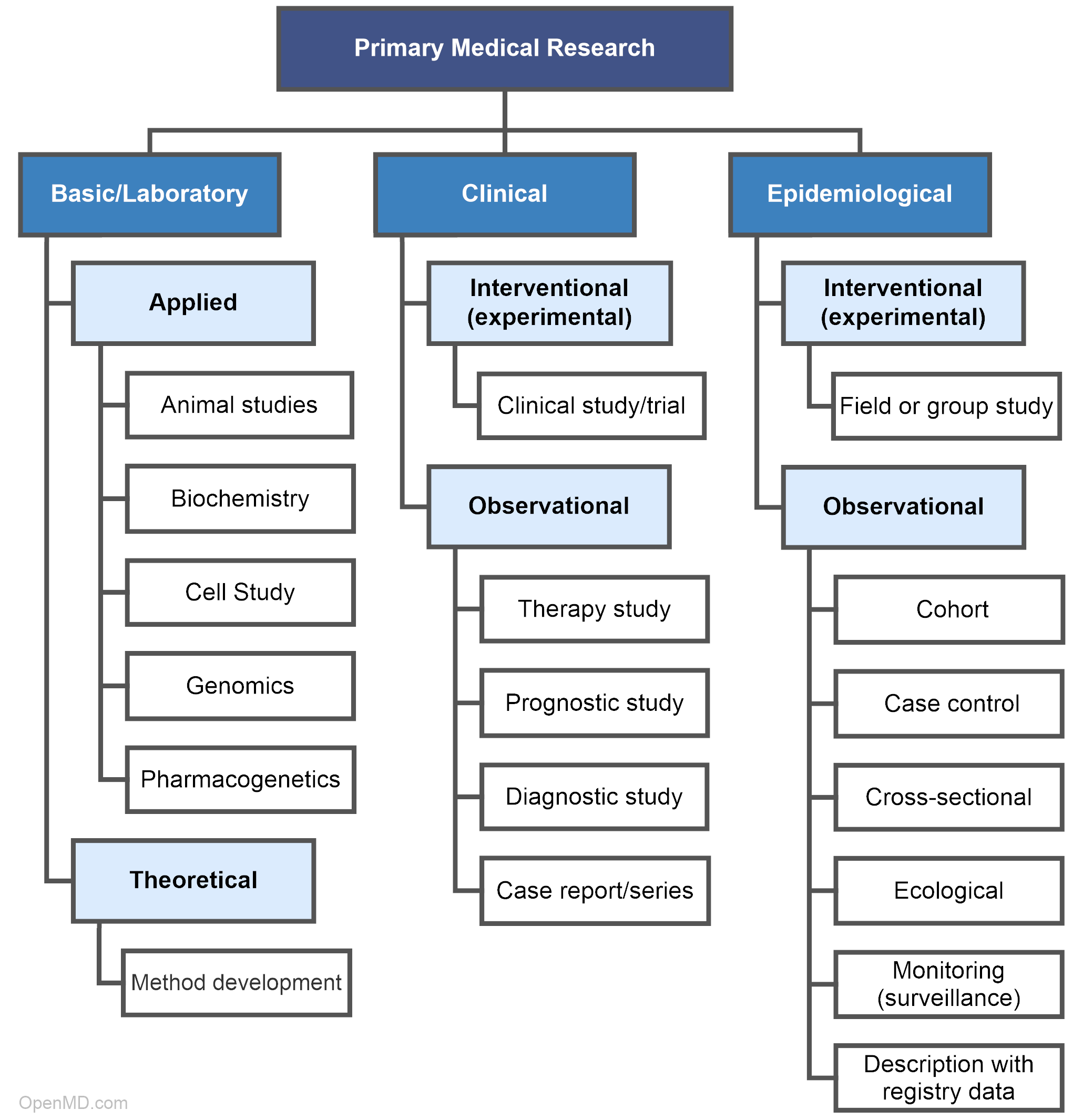

Medical research may be classified as either primary or secondary research. Primary research entails conducting studies and collecting raw data. Secondary research evaluates or synthesizes data collected during primary research.

Primary medical research is categorized into three main fields: laboratorial, clinical, and epidemiological. Laboratory scientists analyze the fundamentals of diseases and treatments. Clinical researchers collaborate with participants to test new and established forms of treatment. Epidemiologists focus on populations to identify the cause and distribution of diseases.

Basic/Laboratory Research

Laboratory, or basic, research involves scientific investigation and experimentation in a controlled environment to establish or confirm an understanding of chemical interactions, genetic material, cells, and biologic agents—more specifically, the agent’s relationships, behaviors, or properties. Basic science forms the knowledge-base and foundation upon which other types of research are built. Laboratory scientists investigate specific hypotheses which contribute to the development of new medical treatments.

An advantage of this type of research is that scientists can control the variables within a laboratory setting. Such a high level of control is often not possible outside of the laboratory. This leads to greater internal validity of a hypothesis and allows the testing of various aspects of disease and potential treatments. The key to laboratory research is to establish at least one independent variable, while holding all others constant. The standardized conditions of a laboratory setting also support the development of new medical imaging and diagnostic tools.

Applied

Applied research aims to solve problems such as treating a particular disease that is under investigation. There a number of different study types within applied research, including:

- Animal studies: Animals are often induced to have a particular disease model so that the disease and potential treatments can be better understood for use with humans.

- Biochemistry: Focuses upon the chemical processes that occur within the body; biochemistry also explores the metabolic basis of disease.

- Cell study: Examines how cells develop and each cell type’s potential role in disease or treatment.

- Genomics: Explores how all genes interact to influence the growth, health, and potential disease development of an organism/human.

- Pharmacogenetics: Pharmacogenetics seeks to better understand the influence genes have upon how a patient might respond to any treatments they may receive.3

Theoretical

Within this branch of research, theoretical approaches are used to develop methods which underpin other types of research. Scientists in this field apply a host of disciplines (including physics, chemistry, biology, bioinformatics, and psychology) to improve the analytical measurements and tools used within research studies. Theoretical research has enabled improvements in our understanding of gene markers and gene sequencing, as well as more detailed imaging procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging. Improvements in statistical analysis and modeling have been supported through theoretical research.

Clinical Research

Clinical research is conducted to improve the understanding, treatment, or prevention of disease. Clinical studies examine individuals within a selected patient population. This type of research is usually interventional, but may also be observational or preventional. In order to categorize clinical research, it is useful to look at two factors: 1) the timing of the data collection (whether the study is retrospective or prospective) and 2) the study design (e.g. case-control, cohort).4 Study integrity is improved through randomization, blinding, and statistical analysis. Researchers often test the efficacy and safety of drugs in clinical drug studies. Many clinical trials have a pharmacological basis. In addition, clinical studies may examine surgical, physical, or psychological procedures as well as new or conventional uses for medical devices. Researchers may perform diagnostic, retrospective, or case series observational studies to diagnose, treat, and monitor patients.

Treatments, dosages, and population can be exactly specified to control or minimize internal differences aside from the treatment.

Interventional/Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are defined by phases, with the first phase (Phase I) being the introduction of a new drug in to the human population. Before Phase I, animal testing will have been undertaken.5 Phase I is conducted to assess the safety and maximum dosage that a majority or a significant portion of patients are able to tolerate. The following list describes the key elements of each clinical trial phase.7

- Phase I: This is the initial step in any drug development, a Phase I clinical trial includes a small number of people (usually 20-100) to determine the safety of a drug and the appropriate dosage.

- Phase II: After success at Phase I, Phase II trials include larger groups of individuals (~100-300) and work to determine both efficacy as well as potential adverse reactions.

- Phase III: At this stage, larger numbers of individuals (~300-3,000) with a specific condition are included within the trial. Trials seek to establish intervention effectiveness in treating a condition under normal use and to establish more robust safety and side effect data.

- Phase IV: Following approval for public use, Phase IV trials are undertaken to understand the long-term impact of an intervention. At this stage, the drug may also be tested on “at-risk” populations, such as the elderly, to make sure that it is safe for a broader population.

Observational

In observational studies, the researcher does not seek to control any variables. Instead, the researcher observes participants (often retrospectively) over a specified period of time. In contrast to controlled and randomized interventional studies, treatment decisions are left to the doctor and patient. Comparisons may be made between individuals given two different types of therapy or having different prognostic variables (e.g. a particular condition). Diagnostic studies evaluate the accuracy of a diagnostic test or method in predicting or identifying a specific condition. Once a number of studies have undertaken an analysis of a single variable, a secondary analysis can take place either via a meta-analysis or literature review in order to see if there is consistency across study results.

Epidemiological Research

Epidemiologists investigate the causes, distribution, and historical changes in the frequency of disease. For example, researchers have looked for trends in cancer or flu outbreaks to determine their cause and ways to prevent or reduce the spread either of these types of disease. These studies can be interventional, but are usually observational due to ethical, social, political, and health risk factors.

Interventional

- Intervention Study: These studies explore changes in health or disease outcomes after the introduction of a specific intervention. For example, the effect of adding fluoride to drinking water was studied through interventional epidemiologic studies in the United States in the 1940s. Another study undertaken in the U.S. sought to assess how a diet high in fruit and vegetables and low in red meat and processed food might impact sodium levels of individuals when compared with a traditional American diet.6

Observational

- Cohort (Follow-up) Study: Observational studies can include many thousands of individuals and because of this, they can be time-consuming and expensive to undertake. To overcome some of these costs, researchers may choose to focus upon a particular group of people (known as a cohort) and explore the health of this group in relation to specific variables. For example, studies have sought to understand how different levels of exercise improve health outcomes.

- Case control: Particularly useful when seeking to explore rare diseases because the population with the disease has already been identified. The group of individuals identified with the disease is then compared to individuals without the disease with the purpose of exploring how the health outcomes differ between the two groups.

- Cross-sectional: Used to explore the levels of disease within a population (prevalence). Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of what is happening within a particular population at one period of time.

- Ecological: Tend to analyze data from previously published sources in order to explore the health of populations and the potential causes of ill health.

- Monitoring/Surveillance: Many countries record and survey populations in order to fully understand the health of their populations.

- Description with registry data: In the United States, cancer registries collect data about the numbers of cases of site-specific cancers each year. This information can then be used to explore rates of cancer at a local level to examine whether incidence and prevalence are changing over time.

- Röhrig, B., du Prel, J.-B., Wachtlin, D. & Blettner, M. Types of study in medical research: part 3 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int 106, 262–268 (2009).

- Haidich, A. B. Meta-analysis in medical research. Hippokratia 14, 29–37 (2010).

- Ma, Q. & Lu, A. Y. H. Pharmacogenetics, pharmacogenomics, and individualized medicine. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 437–459 (2011).

- Sessler, D. I. & Imrey, P. B. Clinical Research Methodology 1: Study Designs and Methodologic Sources of Error. Anesth. Analg. 121, 1034–1042 (2015).

- Umscheid, C. A., Margolis, D. J. & Grossman, C. E. Key concepts of clinical trials: a narrative review. Postgrad Med 123, 194–204 (2011).

- Svetkey, L. P. et al. The DASH Diet, Sodium Intake and Blood Pressure Trial (DASH-Sodium). Journal of the American Dietetic Association 99, S96–S104 (1999).

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. The Drug Development Process.

Contributors

Vanessa Gordon-Dseugo, MPH, PhD; Grace Satterfield, MS

Published: January 17, 2019

Revised: September 2, 2020